[ad_1]

(Editor’s note: This story is part of a recurring series of commentaries from professionals connected to the cannabis industry. Julie A. Werner-Simon is law professor adjunct at Drexel University’s School of Law, a legal analyst for the “Cannabis as an Emerging Business” class at Drexel’s LeBow School of Business and a former federal prosecutor. This is the second installment of a three-part series. Part 1 explained the different degrees of cannabis legalization in U.S. states.)

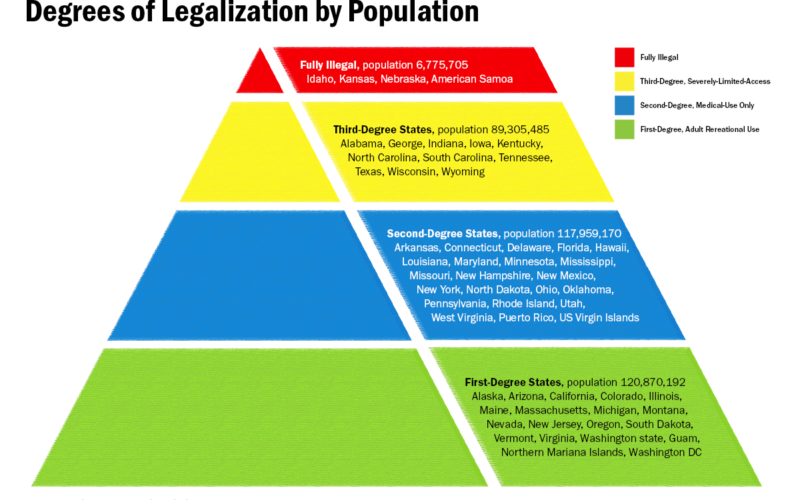

Fewer than 7 million of America’s 335 million inhabitants live in places without some degree of marijuana legalization.

The remainder possess three degrees of legalization. There are 11 third-degree states (depicted in yellow in the pyramid illustration above) with severely limited-access (SLA) programs covering a population just shy of 90 million people.

There are also 20 other states and two territories (Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) that are exclusively second-degree medical-use regimes (shown in blue) and which have a total population of almost 118 million residents.

Finally, there are more than 120 million inhabitants in the 16 first-degree states and territories (the green area in the pyramid), of which all have legalized recreational marijuana use and also have coexisting medical use (second-degree) status.

The apex of the pyramid illustration shows that there are only three mainland-state outliers and one U.S. territory where marijuana is “fully illegal” – that is, being verboten for use in any form.

These are Idaho, Kansas, Nebraska and American Samoa.

But those “entirely illegal” places have stirrings of movement to either third-degree, severely limited access (SLA) – or second-degree medical-use status.

As a general rule, second-degree medical marijuana states and territories permit patients, at a minimum, to possess and smoke medical marijuana, whereas SLAs (such as Texas, which has been in state court this week trying to ban smokable hemp) do not.

Idaho

In Idaho, where the governor vetoed an SLA proposal in 2015 that would have permitted low-THC marijuana for use with epilepsy, residents are seeking reform despite state Republican legislative roadblocks.

If a 2022 marijuana initiative proposal makes the ballot and passes, this will leapfrog Idaho over SLA status and move it directly into the second-degree column.

Nebraska

Roughly 190,000 Nebraskans (more than 10% of the state’s registered voters) signed to place a medical-use constitutional amendment on the 2020 ballot.

However, in September 2020, law enforcement sued to block the ballot initiative.

The Nebraska Supreme Court, on “procedural grounds,” kept the measure off the ballot – holding that it violated Nebraska’s single-subject formalities by seeking to legalize medical marijuana possession and distribution and manufacture.

Unbowed Nebraska residents have proposed another medical marijuana initiative for the 2022 election.

Kansas

In Kansas, where citizens do not have the power to initiate statewide voter initiative measures, legislators last year crafted a medical marijuana bill, but it died in committee.

However, Kansas’ governor recently picked up the mantle and pushed for new medical marijuana legislation arguing that the increased revenue could be used for the state’s Medicaid expansion and a new medical marijuana measure was introduced at the Kansas statehouse last month.

And this month, Democratic lawmakers in Kansas introduced legislation to legalize recreational use.

American Samoa

Because of budget shortfalls, there is even discussion of legalization in American Samoa, an American territory in the South Pacific roughly 5,000 miles west of California. American Samoa, comprised of roughly 55,000 people, is the only inhabited U.S. territory where its residents are born on “American soil” but are legally deemed noncitizen U.S. nationals.

Federal approach

Now consider the federal government’s approach to marijuana.

To this day, for practically all Americans, it is federally illegal to possess marijuana in any amount. It is illegal to take marijuana on an airplane, to place it in the U.S. mail or to transport it across state lines.

The movement of marijuana between states constitutes “interstate commerce,” which the federal government has regulated since the nation’s founding.

Marijuana businesses cannot get small-business loans or federal COVID-19 relief funds, and they are shunned by the majority of federally insured banks given the possibility of federal money laundering exposure for financial facilitation of a federally illegal drug.

Marijuana businesses cannot declare bankruptcy, a federal economic “privilege” afforded to other American businesses and individuals enabling them to “start over” or retool.

Credit card transactions for marijuana businesses are tricky. But major companies such as American Express, Mastercard and Visa traditionally have not permitted the use of their cards for what appear to be marijuana transactions.

And marijuana, even if used medically, cannot be deducted as medical expenses on federal tax returns.

Marijuana businesses cannot (like other businesses) deduct ordinary and necessary business expenses, a position the Biden administration supported as recently as February.

That’s when Acting Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar submitted a legal brief to the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Standing Akimbo LLC et al. v. U.S., No. 20-645, arguing that under federal law, marijuana remains federally illegal.

As a result, the government reasoned the IRS acted properly in seeking tax records for a “state-legal” marijuana company in Colorado that was under investigation for wrongfully taking impermissible federal deductions.

Additionally, it is illegal for a member of the armed services to use marijuana – it is prohibited by the Uniform Code of Military Justice, Article 112a – and it remains illegal to use marijuana as a federal employee, including those currently working at the White House.

America’s constitutional framework is based on dual and often competing governmental systems: federal and state. Marijuana has been federally illegal for more than 50 years.

None of the state-legalization regimes in the space supersede federal preemption. Anyone (and any business) that ignores marijuana’s federal illegality takes a big risk.

Ignorance is not bliss.

(Watch this space for the third installment of Werner-Simon’s identification of the degrees of legalization in marijuana across the country. Part 3 will detail how, despite recent White House firings for cannabis usage, there is evidence that the federal prohibition of marijuana is on the wane.)

Julie A. Werner-Simon is a legal analyst for the “Cannabis as an Emerging Business” class at Drexel’s LeBow School of Business. She can be reached at [email protected].

The previous installment of this series is available here.

To be considered for publication as a guest columnist, please submit your request to [email protected] with the subject line “Guest Column.

[ad_2]

Source link

Medical Disclaimer:

The information provided in these blog posts is intended for general informational and educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. The use of any information provided in these blog posts is solely at your own risk. The authors and the website do not recommend or endorse any specific products, treatments, or procedures mentioned. Reliance on any information in these blog posts is solely at your own discretion.